Outcross History is an effort to collect the scattered information on known and possible breeds that make up the Chincoteague Pony. If you have any additional information, rumors, or theories you would like to share please contact me. Horse/pony names are linked to pedigrees in the The Chincoteague Pony Pedigree Database, All Breed Database or Misty's Heaven wherever possible.

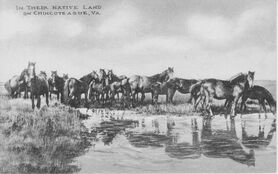

The main and popular story of the breed's early origins is the ponies were from a shipwrecked Spanish Galleon. It is also occasionally stated that the first settlers discovered that Assateague was already inhabited by wild horses. The second origin story is that that Chincoteague and Assateague residents kept their horses (also sheep and cattle) loose on Assateague to avoid fenced livestock taxes. Whatever the origin, it's well documented that there have been feral horses on Assateague since the 1700's.

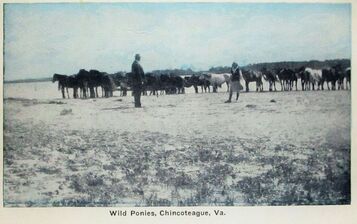

There have been deliberate introductions of different breeds throughout its history, namely by the Chincoteague Volunteer Fire Department, owners pre-dating the Fire Department's ownership of the feral herds, and of private breeders. The outcrossing has been for a variety of reasons, to reduce inbreeding, introduce colors, make up for herd losses, improve breed conformation, etc. Captain William B.S. Powell brought in stock from Pennsylvania, New York, and West Virginia to improve the ponies height. Chincoteagues were considered partbred ponies by most show organizations in the 50's and 60's because there was no studbook or registry. Today they're considered a landrace, a breed that has developed over time adapted to a certain geographic area.

A study published in 1991 titled Genetic Variation and its Management Applications in Eastern U.S. Feral Horses took samples from 60% of the Virginia herd in April 1987. The study found a close genetic resemblance between the ponies and two breeds primarily, the Paso Fino and the Shetland. A genetic resemblance was also found to the feral island herds of Cumberland Island and Ocracoke Island. The study found a higher level of genetic diversity in the herd compared to the other feral Atlantic herds which was possibly "the result of repeated introductions of horses to the island from a variety of sources."

Color can give us some clues as to when outcrossing was done and the breeds involved. Many sources state that the breed was originally all solid colors. Leonard D. Sale wrote in 1896 in The Horse Review of Chicago that, "The prevailing colors are bay, brown, chestnut and light sorrel. I have never yet seen a grey, piebald, dun, or yellow purely bred island pony." However an earlier article from 1891 in the New York City newspaper The Sun stated that the ponies "are most frequently black, gray, sorrel, or dun." A Washington Post article from 1902 stated that the prevailing colors were bay and black and in 1910 the Pittsburgh Times wrote that "Light bays and sorrels predominate. A 1912 Baltimore Sun article stated that the ponies were "black for the most part, white sometimes" and "a dull mahogany red". A fair number of brown bays will be found, while black. White and dun-colored [buckskin] ponies are exceedingly rare." In 1923 a St. Petersburg Times article described the ponies as "bay, gray, dun [buckskin], black, and sorrel", however less than a decade later a Delmarva Star article describing the 1930 Pony Penning described the ponies as "many colored", with blacks, browns, bright bays, and so many with spotted coats. American Wild Horses wrote in 1936 that 50 years before the ponies "were all solid colors: browns, bays, blacks, greys, chestnuts."

There have been several incidents that have greatly reduced the number of ponies in the feral herd and as a result ponies previously sold have been reintroduced and other breeds have also been introduced. A nor'easter in March 1962 killed 55 ponies on Assateague and 90 on Chincoteague. The Wild Horse Dilemma by Bonnie Gruenberg quotes a former Chincoteague resident that due to the decimation of the feral herds after the storm select mares with good conformation were bred to stallions of other breeds. In 1975 almost half of the feral herd tested positive for equine infectious anemia (EIA), also known as swamp fever, and had to be euthanized. 38 Mustangs were added to the herd in 1977 due to these losses. Two Spanish Mustang stallions were donated by Bob Evans in 1976 after he had heard about the EIA losses. The microorganism pythium insidiosum found on Assateague causes the flesh destroying disease pythosis, also known as swamp cancer. Pythosis had killed members of the feral herd over the years, but in the late 2010's there was an increase in infections with eight deaths just in 2018. Several ponies were donated to the feral herd, born both on and off Assateague, to make up for the losses.

Due to the breed's complicated history and the scattered nature of Chincoteague breed registries through the years the boundaries can be muddled as to what ponies are considered partbreds or purebreds. The guidelines used here are if the Chincoteague Volunteer Fire Department, or the feral herd owners prior to their ownership, did the outcrossing then the resulting partbred ponies are considered purebred Chincoteagues. Additionally, if a partbred pony was generally regarded to be a purebred Chincoteague it is considered to be a purebred. There are historical and modern examples of partbred ponies from private breeders that were regarded as purebred Chincoteagues and some that were regarded as partbred.

The main and popular story of the breed's early origins is the ponies were from a shipwrecked Spanish Galleon. It is also occasionally stated that the first settlers discovered that Assateague was already inhabited by wild horses. The second origin story is that that Chincoteague and Assateague residents kept their horses (also sheep and cattle) loose on Assateague to avoid fenced livestock taxes. Whatever the origin, it's well documented that there have been feral horses on Assateague since the 1700's.

There have been deliberate introductions of different breeds throughout its history, namely by the Chincoteague Volunteer Fire Department, owners pre-dating the Fire Department's ownership of the feral herds, and of private breeders. The outcrossing has been for a variety of reasons, to reduce inbreeding, introduce colors, make up for herd losses, improve breed conformation, etc. Captain William B.S. Powell brought in stock from Pennsylvania, New York, and West Virginia to improve the ponies height. Chincoteagues were considered partbred ponies by most show organizations in the 50's and 60's because there was no studbook or registry. Today they're considered a landrace, a breed that has developed over time adapted to a certain geographic area.

A study published in 1991 titled Genetic Variation and its Management Applications in Eastern U.S. Feral Horses took samples from 60% of the Virginia herd in April 1987. The study found a close genetic resemblance between the ponies and two breeds primarily, the Paso Fino and the Shetland. A genetic resemblance was also found to the feral island herds of Cumberland Island and Ocracoke Island. The study found a higher level of genetic diversity in the herd compared to the other feral Atlantic herds which was possibly "the result of repeated introductions of horses to the island from a variety of sources."

Color can give us some clues as to when outcrossing was done and the breeds involved. Many sources state that the breed was originally all solid colors. Leonard D. Sale wrote in 1896 in The Horse Review of Chicago that, "The prevailing colors are bay, brown, chestnut and light sorrel. I have never yet seen a grey, piebald, dun, or yellow purely bred island pony." However an earlier article from 1891 in the New York City newspaper The Sun stated that the ponies "are most frequently black, gray, sorrel, or dun." A Washington Post article from 1902 stated that the prevailing colors were bay and black and in 1910 the Pittsburgh Times wrote that "Light bays and sorrels predominate. A 1912 Baltimore Sun article stated that the ponies were "black for the most part, white sometimes" and "a dull mahogany red". A fair number of brown bays will be found, while black. White and dun-colored [buckskin] ponies are exceedingly rare." In 1923 a St. Petersburg Times article described the ponies as "bay, gray, dun [buckskin], black, and sorrel", however less than a decade later a Delmarva Star article describing the 1930 Pony Penning described the ponies as "many colored", with blacks, browns, bright bays, and so many with spotted coats. American Wild Horses wrote in 1936 that 50 years before the ponies "were all solid colors: browns, bays, blacks, greys, chestnuts."

There have been several incidents that have greatly reduced the number of ponies in the feral herd and as a result ponies previously sold have been reintroduced and other breeds have also been introduced. A nor'easter in March 1962 killed 55 ponies on Assateague and 90 on Chincoteague. The Wild Horse Dilemma by Bonnie Gruenberg quotes a former Chincoteague resident that due to the decimation of the feral herds after the storm select mares with good conformation were bred to stallions of other breeds. In 1975 almost half of the feral herd tested positive for equine infectious anemia (EIA), also known as swamp fever, and had to be euthanized. 38 Mustangs were added to the herd in 1977 due to these losses. Two Spanish Mustang stallions were donated by Bob Evans in 1976 after he had heard about the EIA losses. The microorganism pythium insidiosum found on Assateague causes the flesh destroying disease pythosis, also known as swamp cancer. Pythosis had killed members of the feral herd over the years, but in the late 2010's there was an increase in infections with eight deaths just in 2018. Several ponies were donated to the feral herd, born both on and off Assateague, to make up for the losses.

Due to the breed's complicated history and the scattered nature of Chincoteague breed registries through the years the boundaries can be muddled as to what ponies are considered partbreds or purebreds. The guidelines used here are if the Chincoteague Volunteer Fire Department, or the feral herd owners prior to their ownership, did the outcrossing then the resulting partbred ponies are considered purebred Chincoteagues. Additionally, if a partbred pony was generally regarded to be a purebred Chincoteague it is considered to be a purebred. There are historical and modern examples of partbred ponies from private breeders that were regarded as purebred Chincoteagues and some that were regarded as partbred.

The amount of outcrossing in the feral Chincoteague Pony herd will appear to be lessened based upon the National Wildlife Refuge's 2014 Chincoteague Pony Management Plan. The plan states, "To preserve the integrity of the registered Chincoteague pony breed, the CVFC will no longer introduce foreign stock into the Refuge population. If deemed necessary by CVFC in consultation with a geneticist and the Refuge Manager one "healthy" foreign mare may be introduced to mate with a stallion and give birth. Shortly thereafter, the foreign mare will be transported off the Refuge. The same mare's progeny will remain behind to continue the linage of this new genetic input." The only outside blood introduced to the CVFC's feral herd since 2014 have been off island born ponies and island born ponies donated back.